Amy Ashwood Garvey’s life would be remarkable by the standards of the twenty-first century let alone the first half of the twentieth. Born in Jamaica in the late 1800s, married to the most famous pan-African leader in the world in Harlem, and an active anti-colonial protestor as well as an entrepreneur in her own right, Amy’s international journey has rightly started to gain more attention in recent years. In this post, we consider what happened at the Florence Mills Social Parlour and other key locations associated with her time in London which provide the perfect illustration of how political, social and cultural life collided in this period…

The very fact that Amy moved to London in the 1930s testifies to the city’s growing importance as a location within transatlantic network spanning the Caribbean, north America, Europe and Africa that scholars (following Paul Gilroy’s lead) often term the ‘Black Atlantic’. On a personal level, the move helped Amy move on from a turbulent time in New York City where her short-lived marriage to Marcus Garvey ended in an acrimonious divorce that played out in public, even though he soon ended up in London too!

Setting up in London offered her and on/off Trinidadian partner, Sam Manning, a chance to replicate some of the successes they had begun to enjoy in the US staging plays and musical entertainment. Manning was an interesting character too: he brought calypso music and a flavour of the Harlem Renaissance to Britain, but not everything was imported. In 1935, for example, he staged a show described by the London News Chronicle as the ‘first British negro revue’ where he cast black Britons from Liverpool and Cardiff alongside performers from the Caribbean. Among his more unlikely but influential supporters was Frances Evelyn Greville, the Countess of Warwick, a famous socialite who was the Prince of Wales’ mistress before he became Edward VII.

Amy, meanwhile was still friends with many old acquaintances from the Caribbean and the USA, but her politics had turned to the left since the time of her split from Marcus. She did not reject racial solidarity, but took inspiration from Marx to argue racial oppression should be tackled as part of a wider assault on capitalism and imperialism. She was not the only one to share these views, which were central to the International African Friends of Ethiopia (IAFE), the group Amy helped form in 1935 in response to Italian aggression in Ethiopia.

Although not everyone agreed about how to solve these complicated problems, London was a crucial forum where they were discussed in new ways. The city’s physical spaces – its buildings, streets and public squares – helped many new political relationships form:

This map overlays three key locations in Amy Ashwood Garvey’s London career on top of a heat map of black London’s nightlife, with Soho glowing hot as a centre of jazz clubs, theatres and bottle parties.

Amy’s first business venture was a cafe on New Oxford Street below her flat called the International Afro Restaurant. It opened in 1935 and sat near the border between Soho and Bloomsbury. C.L.R. James was a big fan, remarking later how much he enjoyed the food in contrast to English food which he found ‘uneatable’ (Matera 2015: 146).

In 1936, Amy and Sam set up another venture called the Florence Mills Social Parlour. This restaurant and club was further into Soho on Carnaby Street and was named after an internationally famous African American vaudeville star – another sign Amy was bringing aspects of 1920s Harlem to 1930s London.

The restaurant served food for African and Caribbean clientele. The nightclub, meanwhile, was popular with the growing band of politically aware black people in London. Amy did lots of the cooking herself while Sam ran the orchestra. Even the Fleet Street press started to notice: the Sunday Express reported that ‘race intellectuals from all parts of the world’ gathered at the club (Martin 2008: 140).

Historians often talk – quite rightly – about the connections between social, political and cultural history but its rare to have such a direct case-study as we do here. Amy Ashwood Garvey’s London restaurants provided a forum where black musicians and their artistic expressions operated side by side with radical political activists and their ideas – and surely plenty of others there for the food, company and social ambience.

The benefit of locating these places on a map forces us to think not just about these places as a backdrop, but as part of the machinery that drove this history forward. The locations were not chosen by accident: the economic imperative of setting up in places that would draw a crowd from London’s diverse burgeoning black communities meant these were sensible choices. But more than that, they demonstrate the geographical and political connections between Bloomsbury and Soho, London’s intellectual and cultural hubs, and their relationship with the centre of political power in Westminster. Thinking about the amazing lives of people like Amy Ashwood Garvey in these profoundly local contexts, as well as their globe-trotting counterparts, forces us to think about just how integral the story of black London is to any larger reading of the Second World War.

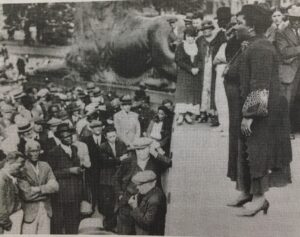

To round off this story, therefore, let’s look at one final location: Trafalgar Square. Here, in the highly symbolic centre of the empire, Amy Ashwood Garvey made the short journey to speak out against Italian aggression in Ethiopia, while drawing connections with injustices closer to home. During one demonstration in August 1935, Amy turned her fire on the white members of her interracial audience: ‘You have talked of “the White Man’s Burden”’, she said, but ‘now we are… standing between you and fascism’ (Matera 2015: 65). The ironic reference to Rudyard Kipling’s infamous justification for empire was telling. The war in Ethiopia did not just ratchet up tensions among the great European powers – it also made many non-Europeans attack the imperial world order as a whole. As Amy wound up her speech, black-shirted British fascists interrupted the rally. They had leaflets that warned blacks to ‘keep out’ of the fight in Africa against what was labelled a ‘degenerate Semitic people’. Black audience members, in response, reportedly seized the suitcase holding the leaflets in protest (Martin 2008: 143). An important reality was revealed in the process: though war was raging far away in Africa, the dangerous ideas that fuelled it could be found much closer to home. As a result, thinking about the lives of people like Amy Ashwood Garvey shows in especially stark fashion how the story of black London was an intrinsic part of the wider history of the Second World War.

Further Reading:

Tony Martin, Amy Ashwood Garvey: Pan-Africanist, Feminist and Mrs. Garvey No. 1: Or, a Tale of Two Amies (The Majority Press, 2008).

Marc Matera, Black London: The Imperial Metropolis and Decolonization in the Twentieth Century (University of California Press, 2015)